| Manu | Date: Tuesday, 08-December-2020, 9:58 AM | Message # 1 |

--dragon lord--

Group: undead

Messages: 13911

Status: Offline

|

A phenomenon first detected in the solar wind may help solve a long-standing mystery about the sun: why the solar atmosphere is millions of degrees hotter than the surface.

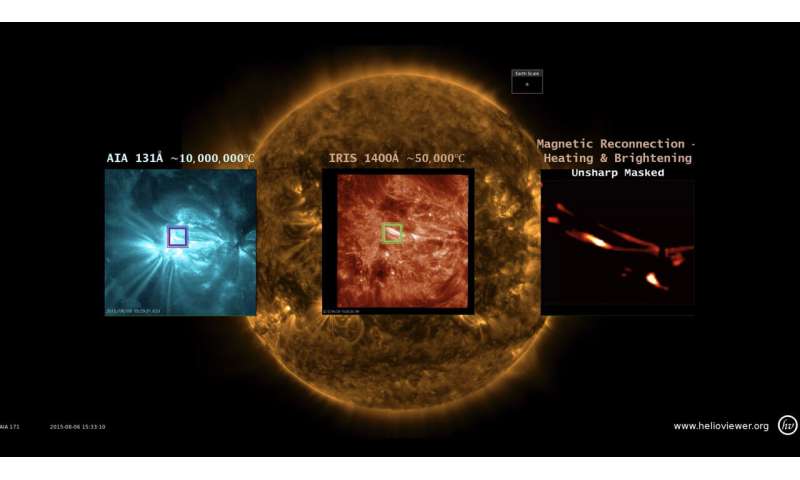

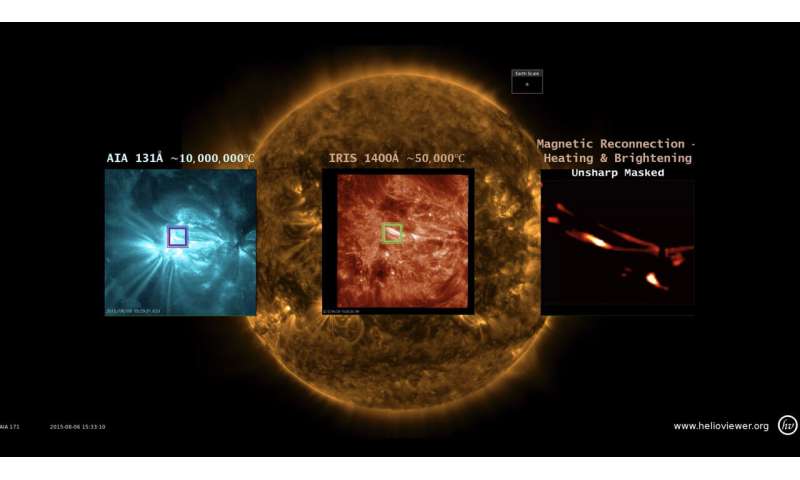

Images from the Earth-orbiting Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph, aka IRIS, and the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly, aka AIA, show evidence that low-lying magnetic loops are heated to millions of degrees Kelvin.

Researchers at Rice University, the University of Colorado Boulder and NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center make the case that heavier ions, such as silicon, are preferentially heated in both the solar wind and in the transition region between the sun's chromosphere and corona.

There, loops of magnetized plasma arc continuously, not unlike their cousins in the corona above. They're much smaller and hard to analyze, but have long been thought to harbor the magnetically driven mechanism that releases bursts of energy in the form of nanoflares.

Rice solar physicist Stephen Bradshaw and his colleagues were among those who suspected as much, but none had sufficient evidence before IRIS.

The high-flying spectrometer was built specifically to observe the transition region. In the NASA-funded study, which appears in Nature Astronomy, the researchers describe "brightenings" in the reconnecting loops that contain strong spectral signatures of oxygen and, especially, heavier silicon ions.

The team of Bradshaw, his former student and lead author Shah Mohammad Bahauddin, now a research faculty member at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at Colorado, and NASA astrophysicist Amy Winebarger studied IRIS images able to resolve details of these transition region loops and detect pockets of super-hot plasma. The images allow them to analyze the movements and temperatures of ions within the loops via the light they emit, read as spectral lines that serve as chemical "fingerprints."

"It's in the emission lines where all the physics is imprinted," said Bradshaw, an associate professor of physics and astronomy. "The idea was to learn how these tiny structures are heated and hope to say something about how the corona itself is heated. This might be a ubiquitous mechanism that operates throughout the solar atmosphere."

Read more/full article/source -

https://phys.org/news....re.html

|

| |

| |